We are very much grateful to many friends, colleagues from a great number of archives, museums and libraries for participating in the exhibition’s development. We have undertaken the best that we could, in order to identify all the copyright’s holders to the works used. Should you be a copyright holder to any of the works, and we have not addressed you, please do not hesitate to address us: info@praguespring68.eu

ABS – The Archive of the Security Services, Prague, Czech Republik

AD – Private collection of Alexander Dimitrov, Bulgaria

AMV Levoča – The Archive of the Ministry of Interior, Levoča, Slovakia

AŠ – Private collection of © Anton Šmotlák, Bratislava, Slovakia

ASZ – Private collection of Stanislav Zibala, Slovakia

AUK – The Comenius University in Bratislava Archive: Photographs collection

AŽSR – The Railways of the Slovak Republic Archiv. Memorial books collection

BS – Private collection of Branko Slukić, Koprivnica, Croatia

ČTK/BTA – Czech News Agency/Bulgarian News Agency

GACY – The Archive of the GACY ’68 project

GI – Getty Images

II – Private collection of Ilija Ilijev, Bulgaria

JP – Private collection of Jana Plichtová, Slovakia

MK – Private collection of Mitko Kalojanov, Bulgaria

MaK – Private collection of Mária Kusá, Slovakia

MMB – Bratislava City Museum

MSFC – Mühlviertler Schlossmuseum Freistadt, Customs Office Archive, Austria

NLA – National Library of Australia

ÖB – Austrian Military Forces

ÖNB – Austrian National Library, Image Archive

PA – Pauer, J.: Praha 1968. Vpád Varšavské smlouvy. Argo 2004, p. 160-161

RHMV – The Regional Historical Museum of Varna, Bulgaria

ŠAK – The State Archive in Košice, Slovakia

SMHA – The State Military Historical Archive, Sofia, Bulgaria

SNM-HM – Slovak National Museum – Historical Museum in Bratislava

SSUA – The sectoral state archive of the Security Service of Ukraine

Sus – Susreti. Glasnik Hrvatsko-českog društva, Nu. 36-37/2019

TASR – The Archive of the News Agency of the Slovak Republic

UKB – University Library in Bratislava, Slovakia

ÚPN – The Nation’s Memory Institute’s archive, Bratislava, Slovakia

ZJ – Private collection of Zdenko Jílek, Daruvar, Croatia

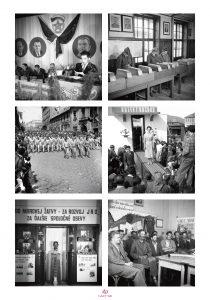

Panel 1

1. The Taste of Power, August 1953 (AŠ)

1. The Taste of Power, August 1953 (AŠ)

2. Still-life in library, November 1955 (AŠ)

3. Long live May 1st 1955 (AŠ)

4. Model, 2. 9. 1955 (AŠ)

5. All for the improvement of Ye-er-d, July 1953 (AŠ)

6. Bread is a Weapon!, July 1953 (AŠ)

over 250 executions were carried out and thousands and thousands of “enemies of the people” were incarcerated in communist Czechoslovakia over a couple of years. Victims could be found on both sides, those of anti-communists as well as communists. Shortly after Josif Stalin’s death, talks on the maleficence of a one man’s concentration of power had emerged in USSR. As for the puppet regimes on its European borders, there had been a variety of reactions to this phenomenon, yet each case differed in its very own way. Even after the death of a „first working-class president“ Klement Gottwald (14.3.1953), there were no significant changes within the upper echelons. The same people who either initiated or/and directed the terror had remained in power. Accordingly, A. Šmotlák’s camera is observing a little change in the framework of the times being. Public spaces are still filled with the same old pictures. There was even no need to “hang down” Antonín Zápotocký in the University library, since he only had changed his position from that of a prime minister to the president.

Yé-er-dé

is a new word in Slovak vocabulary that everybody already knew in 1953. Originally an abbreviation denoted colletive farms, a “cultural” import from Soviet Union. Like many others, this import, too, was accompanied by a violent campaign as well as plenty of people’s tragic destinies. Disclosed by Šmotlák’s camera, though in a solely merciful metaphor, yet it sheds glimpses of a military-like propaganda campaign. Some of the faces depicted in the photograph Bread is a Weapon! elicit an impression that the cooperatives’ problems may reside in the lack of skilled cadres. In fact, cooperatives’ rather poor economic yields caused the process of collectivization to be eased upon after 1953. However, it was about to continue in a short period of time.

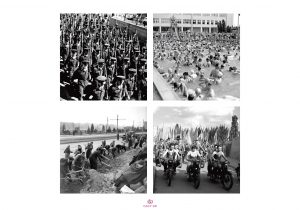

Panel 2

1. Arrayed, May 9th 1959 (AŠ)

2. Let’s go to the pool, Bratislava, July 1958 (AŠ)

3. Equal, 1955 (AŠ)

4. fearless flag-bearers of socialism, 5. 6. 1960 (AŠ)

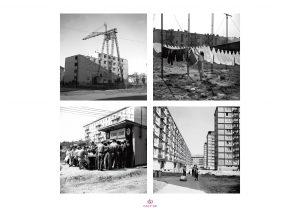

Mass and people’s democracy

belong and will for a long time to the most crucial depictions of public life. Both Soviet “values” and the image of a common enemy are replicated in detail. Strict organization, cult of labour, slogans on a “new human’s” formation, calendar of holidays, scenarios, sceneries and requisites of public ceremonies. Even the Victory over fascism holiday is set to the Moscow time rather than the local one. Šmotlák’s scenes of the construction of new residential houses from 1955 – 1959 serve as a convenient illustration of the regime’s both mass and people’s democratic character. There is a unique shot of a very first prefabricated house (so-called montodom) in Slovakia, framed like an icon: in the centre of a square composition, a crane appears to be dominant while symbolizing a building endeavour. The building’s pioneering relevance is highlighted by the board, however, its message is, unfortunately, poorly readable. The house itself had been built in three months. The pace of the construction was breath-taking, thus creating a lot of hope over the housing policy issues in cities, which were witnessing a rapid growth in population. Šmotlák’s shots, openly, yet graciously, uncover all of the imperfections of the mass neighbourhoods’ fast-paced construction which tended to emerge in the following decades.

Panel 3

1. Building a new world, 7. 12. 1955 (AŠ)

2. Building a new world, 20. 5. 1959 (AŠ)

3. Building a new world, 20. 5. 1959 (AŠ)

4. Building a new world, 20. 5. 1959 (AŠ)

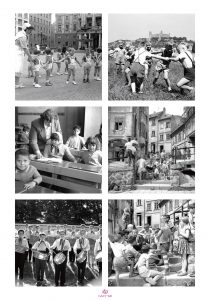

Panel 4

7

7

1. Nursery kids, 15. 8. 1959 (AŠ)

2. Kindergarten kids, 25. 6. 1959 (AŠ)

3. First-graders, 18. 5. 1962 (AŠ)

4. Children, 22. 7. 1959 (AŠ)

5. Pioneers, 5. 9. 1959 (AŠ)

6. Under the castle’s protection, 22. 7. 1959 (AŠ)

Women and raising of a new generation of “builders”

are closely related to the woman’s role in a “new society”. This very issue was a subject to propaganda and its persistence is illustrated by a caricature in one of the women’s magazines Vlasta issues from 1954: the picture shows in one of its fields a pitiful mother with her child in arms who stands in the street below Coca-C writing, in the other, a flock of joyful children in a kindergarten. The “building work” of women and the reality of their gender equality in 1955 is captured by Šmotlák’s snapshot Equal: a front-woman’s smile deeply contrasts the whole scene.

By joining the working process, women’s then traditional roles as mothers had weakened. Children’s upbringing was transferred to a “unified school” since their very early years. The unified education consisted of a uniformed inculcation on happiness, beauty, values, enemies … The photographs show archetypal scenes accompanied by essential requisites, be it either a strictly organized array of drumming kids in pioneer scarves which should have evoked bellicosity, decidedness and readiness to both build and protect, or a bikers’ squad showcasing their physical prowess as socialism’s undeterred colour-bearers. However, the education in schools and families tended to differ in this regard, as proved by youth’s moral stances’ research carried out on a one thousand-pupils‘ and students‘ sample in a much freer and looser atmosphere around 1965-66. It showed, that even after two decades of shaping of a “new man”, stances based on atheism, class consciousness and proletarian internationalism were hardly palpable. Šmotlák’s camera captured the relative imbalance between public and private lives: on one hand, there was an eye-striking uniformity of a “unified kindergarten”, on the other, a real world emerged, that of children with their naturally “disarrayed leisure time”.

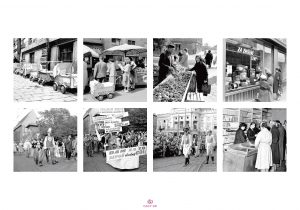

Panel 5

Baby boom, September 1957 (AŠ)

Shopping, August 1957 (AŠ)

A pencil behind an ear, October 1957 (AŠ)

Discount, 25. 4. 1960 (AŠ)

Disguised, June 1957 (AŠ)

Sport – the allowed topic of satire, June 1957 (AŠ)

Student carnival, June 1957 (AŠ)

Broadcloth coats and boredom on sale, 28. 2. 1957 (AŠ)

Baby boom

is dated in Slovakia since 1946, when the number of new-borns had been constantly rising to 100 000. 1957 was the last year to achieve this very birth rate margin. One could easily encounter such baby boom features as emergency lanes for pushchairs. They could have hardly been missed by Šmotlák’s camera lens which positions this scene to the square’s diagonal thus making it yet more impressive. Baby boom emphasized the difference between Slovakia and Czech part of the state where the birth rate had declined by a quarter in ten post war years. Slovakia’s exceptional performance is rather accentuated when put within a broader European context.

More strikingly, the neighbouring Hungary observed a record yearly decline in birth rate by 13% in 1957. Clearly an outcome of the Hungarian revolution drowned in blood by the Soviet invasion. The reproductive behaviour was impacted by open fights as well as their both direct and indirect outcomes not only in the last quarter of 1956 but also in the early months of 1957. The very children born in strong 1946 – 1955 years were going to become instrumental subjects to students’ public discussions, petitions and demonstrations, thus greatly contributing to the public discourse in 1968, as well as the whole ’68 story.

Carnival and political satire

belong together because a mask both anonymously and wittily entitles society to tackle its cumbering issues, while at the same time requiring solutions. The 1957 carnival captured by A. Šmotlák appeared to be a carnival solely from outside. Although students were wearing masks, every one of them knew their impunity was not guaranteed. Thus the procession undertook to mock football, however it failed to address current affairs. A vigorous spark typical for the unfolding years, when students got between wind and water, was yet lacking.

W-coupons,

a word now thoroughly strange, belonged with the reality of the early 50’s. “Wool points”, coupons for a quality woollen textile cloth, which circulated in the times of need, were a much desired item on the black market. Their lack often elicited panic, as it was reflected in Vlasta in 1950: Our women have often been convinced that there is no use of believing in rumours. How many times they have trusted to foreign broadcastings’ information on harsh times to be coming while at the same time buying in panic, and yet the day after they realized that the goods they have bought were rather cheaper big time. The quote reminds us a phenomenon which should not even have existed in the centrally planned economy: if the plan was well carried, there would be no shortcomings. The decrease in prices was a part of the life and the regime took advantage of it politically, rather than marketwise. The monetary reform on 1.6.1953, known as well as money exchange, serves as a textbook case. People lost almost all of their savings which led to open demonstrations. In order to alleviate the general discontent, a massive decrease in prices was ordered, and in the autumn, citizens were confronted with messages such as this: …a discount sale has begun at all retailers across our country. The discount includes more than 23.000 types of commodities, prices of which are decreased by 5 – 40%. Our workers can gain by this decrease in prices Kčs 4.5 bn yearly. The reduction captured by Šmotlák closely preceded the new constitution’s adoption in 1960. The constitution declared a successful completion of socialism in Czechoslovakia, thus the price reduction could have proven it. It is hard to consider what kind of plaiting yarn is depicted in the picture, however the women’s both faces and poses hardly imply it aroused them. In addition, quite a substantial price span is worth noticing. Furthermore, how could an ordinary woman with her salary around 1200-1300 crowns perceive 32 crowns per clew, knowing she would need at least ten of those for a desired jumper? In times when clothes were not imported from China, knitting and sewing contributed to common “pastimes”. Šmotlák’s camera lens took a shot of yet another familiar item, a net bag.

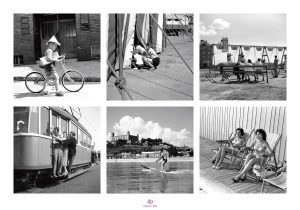

Panel 6

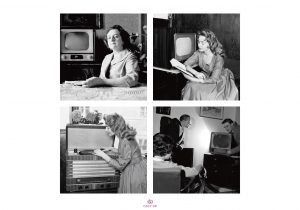

1 Interesting news?, August 1957 (AŠ)

2 The TV is not broadcasting today, August 1957 (AŠ)

3 On the swing, August 1957 (AŠ)

4 Imitation of a forward motion, August 1957 (AŠ)

5 A counterfeit speed, August 1959 (AŠ)

6 Beach equipment ’57, August 1957 (AŠ)

Year 1957

can be despite all of its lethargy described as a year of a certain dynamics. Yet for many it remains undisclosed or appears to be rather flimsy, fake or counterfeit.

The spirit of the time is reflected in Šmotlák’s snapshots that portray an often illusive, mimicked and invisible movement. They capture a variety of contemporary both sceneries and requisites. A human presence brings dynamics to the pictures which otherwise either completely lack it or provide only a putative movement.

It is quite conspicuously depicted in the photograph which could easily be dubbed as Imitation of a forward motion. A wave below a young surfer’s board in the Danube stream invokes an intense feeling that he is moving forward, however in fact, he stands and can only move sideways.

The same fake impression of movement is invoked by a shot of an old Bratislava tram which has been named A counterfeit speed, for the purposes of this very interpretation. A detailed look reveals the tram’s steady position and a motion’s appearance is only present through the passengers’ grimaces and poses, pretending to be travelling at a high speed.

Accordingly, present yet invisible is the dynamics in the scene with boys who are looking below a cover of a big top. One can only feel rather than see it: both tension and concentration with which the boys are watching the arena imply something dramatic happening inside.

The TV is not broadcasting today,

is one of the ways to understand, though with a touch of humour, the picture of boys in a circus. Then, a seemingly “ahistorical” children’s play motive is changed to a clue, directing our focus on a question, how things actually were, concerning television in 1957. Could the boys, at least hypothetically sit in front of a TV? The answer is that in Czechoslovakia there was a television broadcasting in that time, however just 2-3 days a week. In Slovakia, there were something slightly over 30.000 television sets. Thus a television pastime probability was rather a small one.

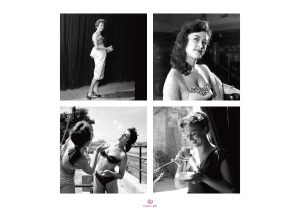

Panel 7

1 Fashion and glamour, November 1959 (AŠ)

2 Fashion and glamour, Maja Velšicová, November 1958 (AŠ)

3 Fashion and glamour, June 1959 (AŠ)

4 Fashion and glamour, Ľuba Baricová, June 1958 (AŠ)

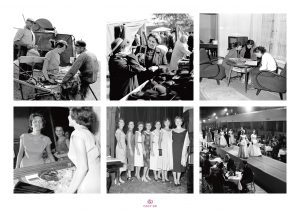

Panel 8

1 I will not tell, July 1957 (AŠ)

2 A look in the mirror, 10. 10. 1957 (AŠ)

3 Learn, learn, learn, April 1957 (AŠ)

4 Fashion and glamour, August 1957 (AŠ)

5 Fashion and glamour, August 1957 (AŠ)

6 Fashion and glamour, October 1957 (AŠ)

Panel 9

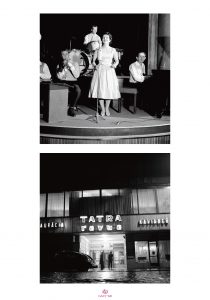

1 Cabaret, Bea Litmanová and Juraj Berczeller, 13. 10. 1959 (AŠ)

2 Tatra Revue, April 1960 (AŠ)

Fashion

and apparel were the areas where the slogans from banners got under the very skin of people. The nature of a socialist man’s and woman’s clothing was “seriously discussed” around 1950. There were radical opinions which understood fashion as something that was not supposed to captivate or surprise but rather as clothing as such, a life need most important right after food.

While the international fashion is becoming a part of both culture and business, women in Slovakia are either queueing in front of the stores or looking for W-coupons. A fashion model on the catwalk captured by A. Šmotlák presents rather a simple and utility-like apparel, hardly a fashion excess. Yet one year later, Slovakia is hit by the news on a brand new Dior collection from Paris. The interview with a French writer Roger Vailland published in Kultúrny život journal in April 1956 bore witness to the fact that a “bourgeois” fashion had naturally been accepted outside the official propaganda. His answer to the question What kind of art issue is debated the most in Paris? needed no further explanation: You are going to laugh – fashion. It is the new line of a tailor Dior. Magazine Express even alleges by capital headlines that introducing these fashion figures has brought tailoring into the very artistic shrine.

Šmotlák’s fashion shows shots from 1957 signify a change in the people’s relation towards fashion. Slow and rather subtle gradualness of the change is reflected in the shop assistants’ broadcloth working coat’s era persistence, as well as in much common lively street scenes complemented by proletarian lifestyle artefacts. A comparison of Šmotlák’s photographs from 1957 and 1959 suggests a surprising “moral loosening” in beachwear. The very fact that Šmotlák found enough models among celebrities willing to undergo a glamour-like photoshoot indicated an end to a puritan moralizing.

Panel 10

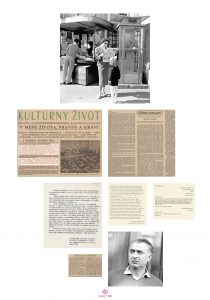

1 Newspaper readers, 1956 (AŠ)

2 Kultúrny život, special issue, 21. 4. 1956, (UKB)

3 Tatarka’s Demon of Consent in Kultúrny život, April 1956 (UKB)

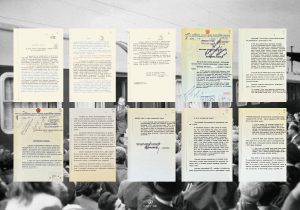

4 The copy of J. Hendrych’s speech, 9.-10. 1. 1958 (GACY)

5 From K. Bacílek’s address at the CC KSS, 26. 4. 1957 (GACY)

6 The censor’s inscription to V. Mináč’s handwriting, 20. 8. 1957 (copy: GACY)

7 Bulgarians criticising “their own Stalin”, Kultúrny život 4. 1956 (UKB)

8 Juraj Špitzer, 19. 10. 1966 (AŠ)

Panel 11

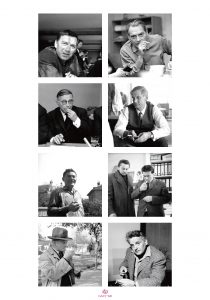

1 Dominik Tatarka, August 1964 (AŠ)

2 Laco Novomeský, 26. 10. 1965 (AŠ)

3 Jean-Paul Sartre in editor’s office at Kultúrny život, 6. 11. 1963 (AŠ)

4 Roman Kaliský, no date (AŠ)

5 Vladimír Mináč, 1963 (AŠ)

6 Miroslav Válek, 26. 11. 1962 (AŠ)

7 Ján Smrek, 17. 10. 1962 (AŠ)

8 Ladislav Mňačko, no date (AŠ)

Getting rid of the “deformations”, and exonerations

tended to become the slogans of the post XX. Soviet communists’ congress era, where Nikita Khrushchev’s speech on Stalin’s regime crimes caused quite a shock. As early as in April, Kultúrny život published Tatarka’s Démon súhlasu (The Daemon of Consent). The readers could get to know themselves in a story of a society living in fear to speak the truth. Writers demanded public discussion. Public discourse was set to a “press censorship” dismissal in art, as well as to political prisoners’ release… The KSČ leadership condemned such discussions, however, Kultúrny život released an answer which refused to put everything back to the same old routine… after a shorter period of time of a freer public discourse.

Discussion on modernity issues

on the pages of Kultúrny život proliferates in 1958. Tatarka, Mináč, Kaliský, Števček, Mňačko, Bžoch… belong to very well-known writers. Modernization is perceived as an opening to the world… Thus, a campaign against Western artistic forms is started. However, it has become rather obvious that the iron curtain has been drawn aside: J. P. Sartre, an existentialist icon, enters Kultúrny život in 1963. An unheard-of thing in Soviet space: people in USSR get to know his work, though to a deformed extent. However, in Slovakia Sartre becomes a talk of the day.

Panel 12

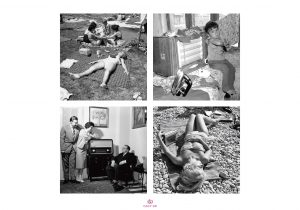

1 A girl with a transistor radio, 28. 6. 1964 (AŠ)

2 Gypsies in Hurbanovo, 18. 5. 1962 (AŠ)

3 At Martin Uher’s place, 5. 2. 1961 (AŠ)

4 Lido, 9. 8. 1962 (AŠ)

Panel 13

1 Hana Meličková, 13. 5. 1961 (AŠ)

2 Filanová, January 1958 (AŠ)

3 Filanová, April 1958 (AŠ)

4 At Martin Uher’s place, 5. 2. 1961 (AŠ)

Radio and television

play even a greater role. By 1966 the number of TV receivers in Slovakia had risen to a half of a million. On could receive a broadcasting from behind the iron curtain in western parts of Slovakia. Vast numbers of Catholics even watch the Pius XII.’s burial on Austrian TV in 1958.

Naša móda

a well-established fashion magazine offers their mostly women readers an elegant solution promoted by the French magazine “ELLE”. The editor’s intention to introduce a regular column Glancing through French magazines illustrates our reader’s rather high demand. It has been introduced with words: Paris… a fashion capital, a good deal of fashion experiments’ incubator as well as excesses…. Anything similar would hardly be imaginable 10 years before. In 1965, information on Dior collections ARE a common thing: silk and woollen accessories inspired by a renowned fashion house CHRISTIAN DIOR are put in spotlight. Antonín Novotný’s era finds its end in fashion much earlier than CC KSČ January plenum took place.

Even the new film wave

serves as a highly pronounced pursuit of an answer to foreign film trends, as well as an example of a yet more intense communication with a formerly wretched part of the world. The first film of the new film wave – Uher’s Slnko v sieti – is dated back to 1962. However, more authors unfolded, mainly Forman, Chytilová, Menzel, Klos, Hanák, Herz, Jakubisko, Kadár… and their original masterpieces accompanied by their both genuine poetry and form had made a worldly impact. World media celebrated The Shop on the High Street as well as Closely Watched Trains both of which were eventually awarded with the Oscar.

Panel 14

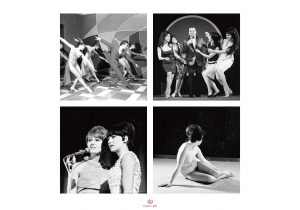

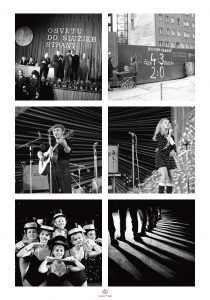

1 Ballet in Hotel Jalta. 24. 2. 1967 (AŠ)

2 Tatra Revue, Adam’s rib, 23. 2. 1966 (AŠ)

3 Bratislava Lyre, Helena Vondráčková, Marta Kubišová, June 1966 (AŠ)

4 Act, without date (AŠ)

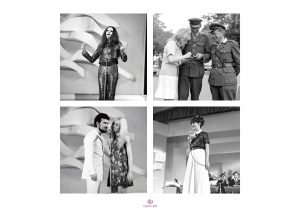

Panel 15

1 Bratislava Lyre, Marta Kubišová, June 1968 (AŠ)

2 Nratislava Lyre, Eva Pilarová and the policemen, June 1967 (AŠ)

3 Bratislava Lyre, Helena Vondráčková, Waldemar Matuška, June 1968 (AŠ)

4 Bratislava Lyre, Jarmila Košťová, June 1968 (AŠ)

Panel 16

1 The beat band Credo chronicle, 1968-69 (ASZ)

2 Stanislav Zibala and Credo, a beag-beat mass (ASZ)

3 – 8. The band Credo (ASZ)

9 The bishop Ján Chryzostom Korec in prison, 1960 (ÚPN)

Life in music

in the late 50’s witnessed a forward nudge and in the course of a couple of years a “covered approach” atmosphere was about to radically change. In 1958 a cabaret in Hotel Tatra is opened with Juraj Berczeller providing music production and many contemporary, as well as soon to be, legends performing. Among many more, František Krištof Veselý, Zuzka Lonská, Eva Kostolányiová, Hana Hegerová …

Additionally, the lyricist Rudolf Skukálek had started his career in here. However, he is more associated with the forthcoming chapter in history of music, which had rather belonged to rock music, the so-called beat, as it was dubbed in Czechoslovakia in order not annoy the censorship with the very word rock.

Beat blossom

in the 60’s brought a solid eruption of beat bands across the country. Their names, such as The Phantoms, The Meditating Four, The Buttons or Blues Five, would clearly refer to both rock ’n’ roll music and Mersey beat as well as to their role models, The Beatles, Rolling Stones and The Who. Bratislava would witness a Beatle craze-like atmosphere thanks to The Beatmen

lead by Dežo Ursíny. Hendrix-like young music’s performances were brought in by a young guitarist Jozef Barina. Moreover, the icon of the contemporary Slovak music Miroslav Žbirka had also kicked off his career in beat bands.

To score a record in the Czechoslovak’s broadcasting services’ studios would be a dream of many beat bands. Some of them have really achieved this goal, yet only the band Prúdy released the whole album under the brand Supraphon. It got dubbed by the leading song Zvonky Zvoňte, to which the lyrics was written by the very Rudolf Skukálek. Twelve songs, many of them iconic, represent the synthesis of the great lyricists’ generation (Peteraj, Filan, Skukálek, Masaryk) accompanied by the great musicians’ flair, such as that of Marián Varga, Pavol Hammel, Vlado Mallý, Peter Saller and Fedor Frešo, to name a few. The album is considered one of the best Czechoslovak albums of the 60’s generation. The beat’s blossoming years had ended with the ascend of the normalization era represented by the “new Reality”. English lyrics were no longer tolerated, long hair became unacceptable. Zvonky Zvoňte ended up blacklisted. Beat musicians had either sprawled into dance orchestras or ceased to play and moved to different professions. Many of them would emigrate, like Skukálek and Berczeller. Tatrarevue was closed. Perhaps, the cabaret’s very own history frames the whole ’68 story, from its very emergence to the crisis and the normalization’s ascend. The last performance bore the title Salto mortale. Its content came in for as an allusion of the occupation in 1969.

Bratislava Lyre

as one of the fruits of the great awakening had become the most significant international festival in Czechoslovakia since its first year in 1966. The stage is offered to both national and foreign top interprets. Thanks to Bratislava Lyre, the domestic audiences gets to know live performances of Cliff Richard, José Feliciano, Gilbert Bécaud, Julie Driscol or Sandie Shaw, Shadows, Tremeloes, Beach Boys, Les Humphries Singers… The venue elicited even Dežo Hoffman, born in Banská Štiavnica, who served as a court photographer for The Beatles, thus bringing a great deal of music business’ contacts from abroad. After his encounter with the festival’s founding fathers, Ján Siváček and Pavol Zelenay, the cooperation grew even more intense while at the same time bringing in a number of global icons to Bratislava.

Panel 17

1 Khrushchev and A. Dubček at the Slovak National Uprising celebration in Banská Bystrica, 29. 8. 1964 (GI/Slovfoto)

2 “Interrupted” G. Husák’s speech at the KSS conference in Bratislava, 4. 4. 1964 (GACY)

3 Revealing of the K. Šmidke’s tablet, 21. 1. 1967 (MMB)

4 Behind bars, 1958 (AŠ)

Exonerations of the 50’s terror’s victims

belong to a great extent to the very story of the ’68. They lied in the centre of the kernel fight within the KSČ ranks for many years. Moreover, two emblematic figures’ destinies in the recent Slovak history are deeply connected to this issue, namely Alexander Dubček and Gustáv Husák.

Dubček experienced the Khrushchev thaw’s turmoil in the flesh while acceding the political studies in Moscow in 1955. On his way back, he had found himself in a situation of no thaw at all. The exonerations of Stalinist terror’s victims were to become one of his signature policies, since yet to 1963 both initiators and directors of the previously carried-out terror were stuck with their positions.

The very struggle for exonerations had persisted through 1963, as Husák and many others got finally exonerated.

The “old cadres” do not favour Husák’s public engagement. His address from March 1964 that sprawled the country in the form of typed copies, is observed with a great resentment.

The issue of the political prisoners’ release as well as their consequent exoneration cannot simply be narrowed to the case of Husák or other communist ranks’ victims. Although together with Husák, 5600 prisoners were released in 1960, yet another 2000 remained in jail. Among others, the bishop Korec, imprisoned in 1960. He was only to be released in 1968, during the Dubček’s era, as the injustices’ atonement would wield rather different environment.

Indeed, when the photographer captured both Dubček and Khrushchev in the same shot, he could have hardly thought that he was making picture of the two main promoters of the two respective “springs”. Nevertheless, even Khrushchev had not anticipated being removed in fewer than two months. Likewise, Dubček could have hardly expected to become an icon of yet another “spring” in couple of years… while eventually ending up “withdrawn”.

Panel 18

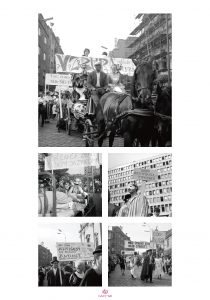

1 Young generation’s revolt, carnival, 5. 5. 1966 (AŠ)

2 Sexual revolution 1, carnival, 5. 5. 1966 (AŠ)

3 Exonerated, carnival, 5. 5. 1966 (AŠ)

4 Sexual revolution 2, carnival, 5. 5. 1966 (AŠ)

5 Students’ voice, carnival, 5. 5. 1966 (AŠ)

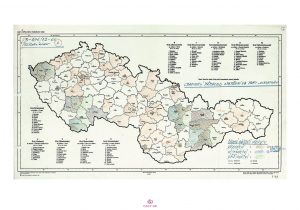

Panel 19

The police map of the “longhaired”, August 1966 (ABS, f. HS VB, internal department – sign. H 1-4, i. j. 776)

The generation gap

accounts for a major feature of the ’68 story westwards of the Iron curtain. It was a year of the youth’s rebellion. Yet in our country there had been a potential for staking out of overlapping generations as it was demonstrated by the students’ carnival in 1966. They provided a declaration of a more open relation to sex, contraceptives as well as other taboos of the society. The “rebellion of the youth” is announced. A generation conflict is obvious when it comes to taste in music: Young people are mad about The Beatles in Bratislava as well as in Hamburg or London. Those who listened to Radio Luxemburg’s hits in the early sixties, had founded their very own bands. The revolt is represented by long hair both abroad and at home. The police map of the “longhaired” bears witness to the particular relation between the police and “hippies” back then. In addition, the very map reflects the bigger cities’ role as a fertile ground for the youth subcultures’ developments.

Panel 20

Dubček and A. Novotný at Devín castle near Bratislava, 4. 6. 1967 (AŠ)

Panel 21

1 Dubček at the Santovka public swimming pool, 16. 6. 1968 (GI/Three LionsHulton)

2 Liberty leading the people?, 1. 5. 1968 (GI/Slovfoto)

“not the big boss type”

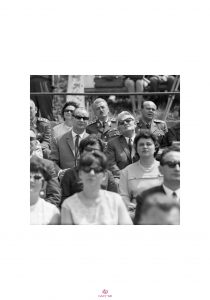

they would write on A. Dubček abroad. The photograph taken in at the public swimming pool in Santovka, and many others, hit the world. Thanks to his fresh and unconventional behaviour which substantially differed from that of the “old ranks”, his popularity had grown. Dubček’s popularity would contribute to KSČ’s improved image both among the Czechoslovak citizens as well as abroad.

May days

would traditionally serve as manifestations of submission: masses would march down the streets, wave and call slogans, and the Party’s dignitaries would condescendingly observe the whole parade from tribunes. The picture which reminds us of the Delacroix’s romantic scene of Liberty Leading the People shows rather a different situation. The leaders are unitedly joined with the procession, even leading it. The necessary requisites in form of the portraits of Lenin, Engels and Marx, are meant to justify the socialism with human face. However, there was more to the respective procession, although not necessarily captured by the photographer’s camera: an American flag over the heads of the marching people. Couple of days later, Brezhnev told Dubček off over it during his visit in Moscow. One year later, in May ’69, bunch of young men held over their heads their very own portraits, instead of those of the proletariat’s leaders. Thus, one can say that the political activism of the ’68 turned into a political prank.

Panel 22

Easing, a popular Slovak actor Milan Lasica at a rehearsal, Bratislava Lyre, June 1968 (AŠ)

Panel 23

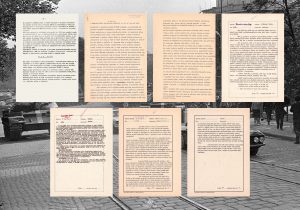

1 Ministry of defence’s note to BĽR on the negative situation in CSSR, 12. 4. 1968

2 KGB information on the church affairs in CSSR (SSUA, f.16-Op.01-Spr.0971-0183 to 185)

3 KGB information on the correspondence’s surveillance (SSUA, f.16-Op.01-Spr.0971-0140 to 144)

KGB perlustration of the letters

A CSSR citizen, V. K., writes in her letter to Ukraine: “CSSR has been a subject to a coup. All of the Party and state leaders have been accused and removed from their positions, even the the highest one, comrade Novotný. One can only guess who speaks the truth. The pioneer brigades have been dismembered, too. People tend to blame the USSR. It is hard to believe that this could happen, however it is true. Earlier before, the working class had been represented within the top ranks, now it is no longer the case. I am not sure if it will be better for us but I doubt it. I am surprised that the Soviets could allow this to happen.”

A Ukrainian living in Czechoslovakia, V. Ž., comments on the events in CSSR as follows: “We undergo a real cultural revolution in here. Everything moves in a radical way, top-down. Freedom of speech, dismissed censorship, no more unity in thinking, opposition, a free parliamentary debate, freedom of travelling abroad, the big brother is gone, federation, Czecho-Slovakia, not Czechoslovakia, social democracy… It will influence the rest of the world.”

On church affairs

…among one of the students’ requests, one could find an adoption of religious freedoms. They had also requested the cardinal Beran’s return from Vatican in order to take over the Church’s administration. In March, the Czechoslovak press brought news on the administrative dismissal of the Greek Catholic church in Slovakia, the Greek Catholics … ran an active campaign for their Church’s renewal. Their representatives started to collect petition sheets calling for their support… The Orthodox clergy held an impression that their Church would then be barely able to exist. Panic began to spread among Orthodox priests.

Panel 24

1 Communist parties’ leaders in Bratislava, 3. 8. 1968 (GI/Schirner)

2 Alexander Dubček is leaving for Čierna nad Tisou (GI/H. Redl)

3 A welcome at the railway station, 2. 8. 1968 (GI/Keystone-France)

4 Kosygin, Brezhnev and Dubček are walking towards Slavín (GI/PhotoQuest)

5 The invitation letter, no date (copy and signature according to PA)

Visit of the Slavín memorial

The Bratislava brother parties’ assembly listed the visit of this iconic site for solidarity and commemoration of the fallen Soviet soldiers to the programme of the meeting taking place in August 1968. It had been the last one of the Soviet bloc’s countries’ common meetings in a row: Dresden, Moscow, Warsaw… Its reason was to nudge the Dubček’s administration onto a rather different course. The Soviets had blamed him for their negative media image, weakness in cadre politics, chaos and above all, a danger of a coming counterrevolution. Petro Šelest, one of the members of the Soviet delegation recalls that in between the discussions he was privately dropped an invitation letter by Vasil Biľak, at the restroom.

In the first row from left to right: János Kádár, Nikolai Podgorny, Alexei Kosygin, Todor Zhivkov, Ludvík Svoboda, Leonid Brezhnev, Wladyslaw Gomulka, Walter Ulbricht, Alexander Dubček, Mikhail Suslov, Piotr Shelest. The second row: Josef Smrkovský behind Brezhnev, Erich Honecker behind Ulbricht.

The meeting in Čierna nad Tisou

was a substantially less grandiose one. The Soviet delegation was accommodated in a luxurious train in Čop and would attend the meetings across the border on a daily basis. The Soviet party would ask question to which both Dubček and Smrkovský could in no way find answers which would satisfy the Soviets. Brezhnev took a direct train to Bratislava.

The invitation letter

constitutes one of the “spicy” issues concerning the very invasion. However, in terms of the situation’s development, its significance appears to be a minor one. Its signatories did not possess the respective powers to take decisions. Furthermore, the decision on a military operation had been adopted way before the letter was transmitted. It was just a cover act serving solely to the propagandist purposes, and yet even with regard to this, the letter had barely brought any major benefit. After all, it is hardly a literary treasure and the author’s language skills is no piece of art.

Panel 25

1 We trust in you. May you trust in us, August 1968 (AŠ)

2 Hot summer, 30. 6. 1968 (AŠ)

3 The down-trodden names, August 1968 (AŠ)

Panel 26

Panel 27

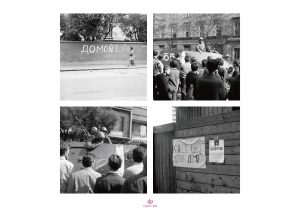

1 Go home, August 1968 (AŠ)

2 Tapping all over, August 1968 (AŠ)

3 Dialogue, August 1968 (AŠ)

4 Biľak – the traitor, August 1968 (AŠ)

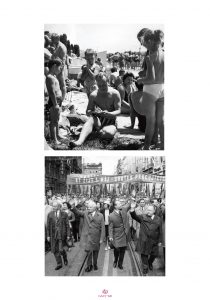

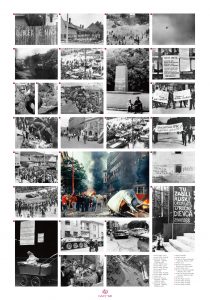

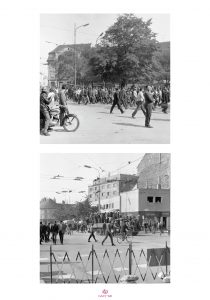

Railwaymen’s memorial books

had justified the “international brotherly help”. In fact, not all of the Dubček’s era novelties were generally admired. People could have opposed a variety of features: from a negative stance on nudes appearing in magazines, through the USSR being subjected to a harsh criticism in media, to the approval of federalisation as well as with the “chaos” that must have necessarily been brought into the society used to “unity” of opinion, by the very process of democratization. Attitudes to the changes varied depending on the generation , nationality or the level of education. Thus, those KSČ high ranks’ members who had requested the “help”, must have counted on the society’s part’s backing, yet a silent one. Nonetheless, the internal criticism of the Czechoslovakia’s reforms had been taken advantage of by the contemporary Soviet propaganda. Despite such voices, it is rather obvious, according to vast amount of facts and materials, that the population’s indignation had reached mass scales and the opposition to the invasion was practically unanimous among the social strata. Hundreds of petitions and declarations had been organized both in cities as well as in the countryside, and various age and social groups had been joining in.

Panel 28

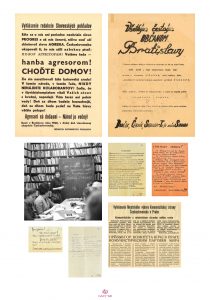

1 Slovenské pohľady journal’s declaration from 22. 8. 1968 (SNM-HM, e. č. H 33688)

2 To all the honourable citizens of Bratislava (SNM-HM, without number.)

3 You will see, you might as well need the Russian language, 1966 (AŠ)

4 – 7. The leaflets distributed among the occupation armies’ soldiers, 29. 8. 1968 (SSUA, F.16-Op.01-Spr.0976, l. 352-3, 355, 359)

8 The special issue of Národné noviny journal from 21. 8. 1968 (SNM-HM, without number)

While the courageous words

of the editors of the journal Slovenské pohľady bear witness to the aroused atmosphere, the occupation’s second day’s general strain as well as the spirit of betrayal and insult, Russian leaflets and the Národné noviny’s article set in Russian, though carried out erroneously, they all speak of a naïve belief that the occupation armies’ soldiers could be convinced of the invasion’s very illegitimacy.

7 Soldiers! If you are true friends, go back home! We all want Dubček, Smrkovský and all of our state representatives. Our nation wants to work in peace. We want socialism, yet our way. Therefore, go back home! Long live Dubček, Svoboda!

Panel 29

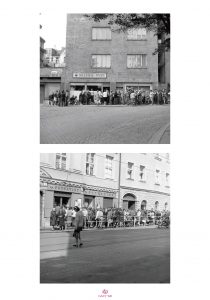

1 Everybody out! 1, August 1968 (AŠ)

2 Everybody out! 2, August 1968 (AŠ)

Panel 30

1 A shopping panic 1, August 1968 (AŠ)

2 A shopping panic 2, August 1968 (AŠ

Panel 31

1 Railway station memorial book in Dražovce (AŽSR)

2 Railway station memorial book in Komárno (AŽSR)

3 Railway station memorial book in Šahy (AŽSR)

4 Railway station memorial book in Vígľaš (AŽSR)

5 Railway station memorial book in Ruskov (AŽSR)

Railwaymen’s memorial books

have been kept at every single railway station. However, it has been rather a matter of tradition than an administrative duty, thus some of them are more detailed, while others are more general. One can predominantly find resistance and disagreement on the invasion, however there are a few favourable ones. Such is the case of a small rural train station in Dražovce. It is rather difficult to recognize if the author expressed his sincere opinion, or if he simply switched his thinking to the newly emerged reality.

Panel 32

1 The ZNB (National security corps) report on citizen’s protests, 2 letters, 6. 11. 1968 (ÚPN, R 012, inv. č. 210)

2 The burial of Jozef Svijetel, 28. 11. 1968 (TASR)

3 The traffic signs yet again in their right places, 6. 9. 1968 (TASR)

4 The place of Danka Košanová’s death (AUK/Jozef Malacký)

5 Damaging of the five-pointed star, 29.-30. 9. 1968 (ŠAK, f. VB Košice)

6 Writings on the dignitaries’ houses, 24. 9. 1968 (ŠAK, f. VB Košice)

7 Burglaries, 22.-23.8. 1968 (ŠAK, f. KS-ZNB, Správa VB Košice)

8 Personal freedom infringement, rioting, 28. 8. 1968 (ŠAK, f. VB Košice)

9 A Soviet car crashing, 5. 9. 1968 (ŠAK, f. VB Košice)

10 Damaged gravestones, 30. 8. 1968 (ŠAK, f. VB Trebišov)

11 Singing of the national anthem, 6. 11. 1968 (ŠAK, f. VB Prešov)

Panel 33

1 The mass gathering at the M. R. Štefánik’s memorial, 5. 5. 1968 (TASR/J. Smolka)

2 University students’ gathering in Nitra, 22. 3. 1968 (SNM-HM, e. č. H 56273/J. Bakala)

3 University students’ gathering in Bratislava, 8. 1968 (SNM-HM, e. č. H 56274/A. Prakeš)

4 A call on the youth from Trnava region, 1968 (SNM-HM, e. č. H 33685)

5 Measures taken by VB (police) in Stará Ľubovňa concerning Jan Palach’s death (ÚPN, f. KO-ŠOH Košice, inv.č. 439)

6 Stanislav Fila, the father of the idea of a hunger-strike for Jan Palach, January 1969 (JP)

7 Jana Plichtová, the hunger-strike for Jan Palach participant, January 1969 (JP)

8., 10. A tribute gathering in front of the University, January 1969 (AUK)

11 The hunger-strike participants, January 1969 (JP)

12 The hunger-strike against the occupation, 25. 8. 1968 (GACY)

The French May ‘68

as well as the rest of the European student movements had endorsed radical leftist ideologies. Somebody wittily created a new ideal political figure, Ho Che Mao, out of their political hero’s names. This could have hardly been imaginable within a leftist dictatorship environment, in our country. And yet, the youth’s political activism was enormous during the year 1968. The photographs show that the students’ rallies, demonstrations and debates tackled a variety of issues, among many Novotný as a symbol of the old-school communist regime, Štefánik as a Slovak national hero, tabooed for a long time by Czech political elites, and federalization as a way of solving the ethnic question in Czechoslovakia. The generation gap appears to be absent in political topics, and both students as well as older generations articulated the same demands: freedom, democratization and fairness in every single concern. Within the existing political realm, students tended to project their hopes into socialism with a human face. Thus, the invasion was to be felt by the young generation as a crush-down of their ideals yet more intensely.

We have to be the generation which will stand its ground, somebody wrote on a poster. It is exactly the apathy in which the society had found itself after the invasion, to which Jan Palach’s act as well as his farewell letter were an answer. Palach’s sacrilege is waking the society for a certain amount of time and the youth is becoming active yet again. The Comenius University students’ hunger strike is thus a declaration of a generational responsibility … as well as difference.

Panel 34

1.-2. Pious place of Danka Košanová’s death, January 1969 (AUK)

3 A call on hunger-strike, 20. 1. 1969 (AUK)

4 Pious place of Danka Košanová’s death, January 1969 (AUK)

5 Art students’ reaction to Jan Palach’s deed (JP)

6.-15. The funeral march for Jan Palach (AMV Levoča)

Eye-witness’ memories: Jana Plichtová on Jan Palach

… His sacrifice affected everyone, even Husák himself felt it. I recall his voice shortly after Jan Palach’s deed, as he called for society’s reticence. He appeared to be unusually quiet and gentle. Palach’s act, in its radical finiteness, was above all a great challenge for his generation as it held a mirror up to its conscience, courage, audacity and solidarity.

At the same time, it was a call for life in truth and freedom.

… Some students debated the event at the legendary wall in Gondova street near the Faculty of Arts, where many couples had arranged their first dates, while others were orchestrating particular plans in a near, notoriously known pub. Those were the places where the idea of a hunger strike together with honouring Palach’s act had come to its life. And so, thanks to our organizational talent as well as an intense networking of Stanislav Fila and others, we had assembled a catafalque, black cloth, condolence book, both state and academic flags. The very next day, the 20 January, we had begun a hunger strike.

… Hundreds of people were pouring towards the Comenius University’s main building, just to express their compassion and to add their signatures into the condolence book. Some of them were there just to talk. We were cold, since the foyer was not heated and the door was wide-open, we were suffering from hunger, and at the same time we were annoyed by some people’s doubts on our sincere intentions to strike, but… one could have hardly compared the hardships with those of Jan Palach.

… One thing I know for sure. Jan Palach has inserted a valuable message to my mind. In particular: one must fight for their freedom, humane society stems from its very concrete deeds, everyone carries a burden of responsibility for the kind of society we live in. Every one of us can be an inspiration for the others.

Panel 35

1 The 22nd motorized striking regiment’s military operation’s diary (SMHA, f.343, op.XIV, a.e.4)

2 An excerpt from the personal notebook of the 22nd motorized striking regiment’s soldier (II)

3 Report on political activities within the Bulgarian armed forces (SMHA, f.3, op.6, a.e.74, l. 252)

4 The 22nd motorized striking regiment’s command No. 8, 27. 9. 1968 (SMHA, f.24, op.10a, a.e.22, l. 155)

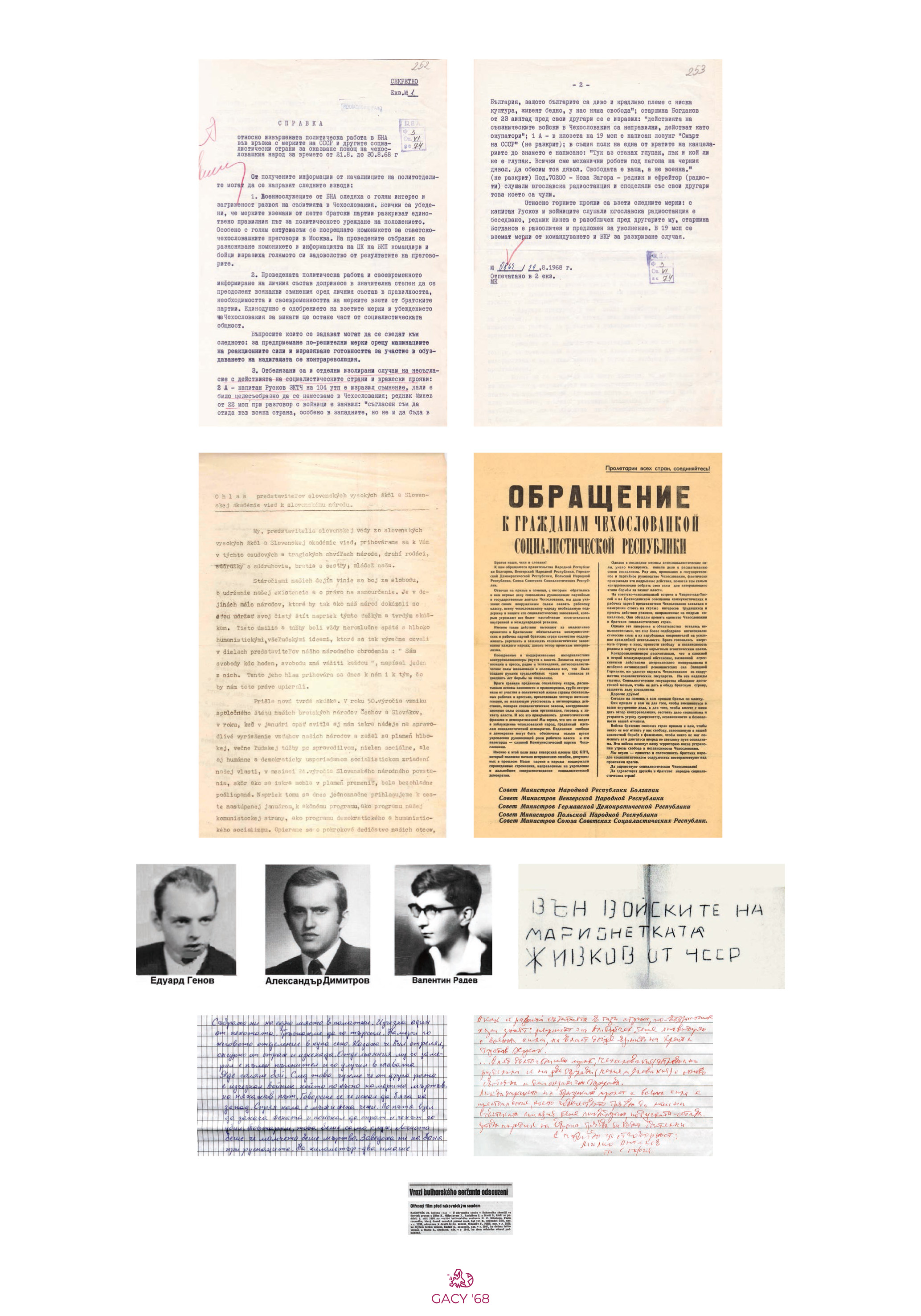

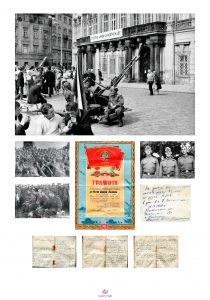

Bulgarian armed forces

were „represented“ at the Operation Danube by a tank battalion consisting of 26 T-34 units, the 12th motorized striking regiment (1206 soldiers) and the 22nd motorized striking regiment (962 soldiers). The task of the 12th regiment which operated in Slovakia, was to beset Zvolen, Banská Bystrica and Brezno. The task of the 22nd regiment was to control airports Ruzyně and Vodochody.

The military operation’s diary

which has been preserved, describes in 96 pages both military operations and the regiment’s activity from their departure from Bulgaria on 2.7.1968 to their return back home on 30.10.1968. Besides the many routine activities’ descriptions, it includes, for instance, a record of the shooting from 23.8.1968, when a group of 10 people approached the Ruzyně airport, began to shoot and after that they moved into the woods. The following extract is from the writings to 20. And 21.8.1968:

The regiment has settled in the camp near the Kolomyia airport (Ukraine, former USSR), in the tents that had been prepared in advance by the 38th guardsmen regiment’s Soviets soldiers. We have been welcomed as real brothers. We have even organized a couple of sport matches with the Soviet soldiers, set a good deal of common cultural events, as well as friendship meetings. On 20.8.1968 at 6:00 pm, while fulfilling its international duty, the regiment got a task to overtake Ruzyně and Vodochody airports in Czechoslovakia. On 20.8.1968 at 8:00 pm, everything was prepared for on-loading. 20.8.1968, the technical equipment was loaded on a first transport line.

Panel 36

1 Branko Slukić’s family gets to know Slovakia, Summer 1969 (BS)

2 The Yugoslav army in position: digging in the howitzers, around 23. 8. 1968 (ZJ)

3 Memories of people who had really helped (Sus)

Tito’s Yugoslavia

was in like manner a favourite holiday destination 50 years ago as Croatia is these days. The borders are open, there are no major obstacles in terms of travelling, both political and economic relations between CSSR and SFRY are quite vivid and the political upper echelons even declare their further improvement. In the midst of August, there are approximately 50 000 vacationists from Czechoslovakia at the Adriatic coast. They are about to feel the very impact of the invasion as their homeland.

Several countries are tightening up their border policies. Austria is closing its Hungarian border, Hungary prevented CSSR’s citizens returning back from holidays from entering their country. Part of them are making it to reach Austrian border, however, plenty of them are stuck in northern Croatia while ending up nearly reaching the border. No money, no food, no roof over their heads. The people from Zagreb, Daruvar, Koprivnica and Varazdin as well as from other inland towns are expressing their unselfish compassion and help. The “Housing staffs” are providing hundreds and hundreds homeless families with accommodation at the locals’ houses. They would wait week or two, until the situation settles.

Many people stayed at the coastal destinations where the situation seemed to offer no chance of return. Rijeka, Krk, Crikvenica, Hvar, Makarska… hitherto, people who experienced the invasion still share their stories. Some of the friendships which had emerged due to exerted emotions of the two first weeks following the invasion, will last for years.

In 1969, Branko Slukić’s family is travelling to visit Laci and Marika from Košice. They are not forgoing a visit of High Tatras. One could observe that such cases were not exceptional. Who knows, how many of our citizens have ever visited the soldiers’ families as an expression of gratitude for their “international help” to our country. Very few, arguably, if so.

Thus, it is worth mentioning the true and generous brotherly help provided by thousands of Croats to the CSSR’s citizens in need.

Panel 37

1 The report on political activities in Bulgarian people’s army (SMHA, t.3, op.6, a.e.74, l. 252)

2 Slovak academics’ declaration and SA, no date (GACY)

3 A call of the governments of BPR, HPR, GDR, PPR and USSR on citizens of CSSR (SNM-HM, ev.č. H 23901)

4 The anti-invasion protest organizers in the centre of Sofia, and a leaflet, 21. 8. 1968 (AD)

5.-6. The excerpts from soldiers Mikhail Milanov’s and Miko Angelov’s memories, 2019 (RHMV)

7 Rudé právo newspaper’s report, 23. 5. 1969 (UKB)

The note on political activities in Bulgarian people´s army

for the period from 21. to 30. August 1968 notices utterances of divergence:

A call to Czechoslovak citizens

which was distributed by the occupation armies stated as one of the reasons for the invasion a “demand for help from the leading party’s and state’s ranks who had truly believed in socialism”, to which it had been an answer.

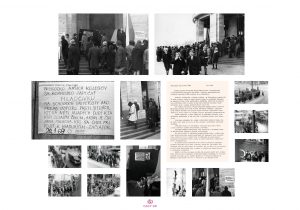

Zhivkov is a puppet

was one of the protest slogans which occurred in the centre of Sofia. Three activists are organizing a student protest against the invasion at the Sofia university.

The case of the sergeant Nikolov’s assassination

belonged to one of the “extraordinary events” of the Danube operation. The offenders was eventually charged with murder. Mikhail Milanov recalls in his memoirs, that he might allegedly have heard it was a case of self-defence, considering that Nikolov was drunk and intended to rape a girl in a car which he had stopped while hitchhiking on his way to leave the battalion.

Panel 38

1 “Soviet art of the 20’s and the 60’s”, August 1968 (ČTK/BTA)

2 – 3. Soldiers must be entertained, August 1968 (MK)

4 The Operation Danube participant’s diploma, 20. 10. 1968 (RHMV)

5 Friend Mitko’s souvenir (RHMV)

6 Mitko Kalojanov’s notebook (RHMV)

An occupation’s routine day

is documented by the photograph of the Soviet soldiers in Prague. It only adds to the irony of it that the very day of 21.8.1968, an opening of the Soviet art exhibition was planned. Thus, instead of the fine art in gallery, the passers-by in Prague could have enjoyed “military art” directly in the square. The occupiers’ armies consisted mainly of youngsters whose military service resided to a great extent in easy military tasks. While executing those, they would often involve with civilians. The hundreds of soldiers needed to be kept occupied and provided with a scheduled programme even in their leisure time. International “friendship” as well as common concerts for soldiers and other cultural events had been promoted rather on purpose. Mitko Kolajonov’s photograph with a dedication, in which he is accompanied by two Soviet boys, show that the “friendship” events were not just a formal showcasing. True friendships could have emerged among young people. However, the best the soldiers could have hoped for was a chance to leave the battalion for a walk-around. After the biggest concernment had fallen off, soldiers were allowed walkouts. However, both our police authorities’ as well as foreign military inspectors’ dispatches disclose repeating cases of the drunk “liberators’” vandalism while out of their barracks.

After the “campaign”

soldiers would receive a diploma for “taking part in providing help to the Czechoslovak brother nation in their fight against the counterrevolution”, which has been kept by Mitko Kaloyanov as a relic, even after fifty years.

Panel 39

1 Border control Berg-Bratislava, 21. 8. 1968 (ÖNB)

2 Refugees in Viennese Stadthalle, 3. 9. 1968 (ÖNB)

3 Radar is monitoring the motion at neighbours, August 1968 (Photo: ÖB)

4 Bundesheer around Allentsteig, Zwettl and Horn, August 1968 (Photo: ÖB)

5 Wullowitz customs office report on trespassers from 21. 8. 1968 (MSFC, f. 1968)

6 A record on an alleged airspace trespassing in Austria, 26. 8. 1968 (MSFC, f. 1968)

The morning of the invasion

the federal chancellor Josef Klaus read the official statement of the Austrian government in which a strict neutrality position as well as independence of Austria were stated. The memorandum highlighted that Austria was not indifferent to other countries’ sufferings, however, it failed to condemn the very invasion. It shows the dilemma of the Austrian government, which on one hand had expressed their intention to improve mutual relations, sympathized with CSSR’s reforms, and understood the whole situation, on the other hand they realized that since the Austrian state treaty and the allied forces’ withdrawal, only 13 years had passed. Austria could have hardly dared to endanger their relationship with the USSR. Same reasons had kept the Austrian army away from the borders, that were instead only protected by the police and customs officers.

The refugee crisis

had yet emerged in the early hours after the invasion, and the following days it continued to grow. The offices had tried to be helpful to the refugees. The number of visa applications was ever growing and both the embassy in Prague and the consulate in Bratislava were issuing the necessary papers without major formalities seven days a week. Charitable collections for refugees were organized. From 21.8 to 23.10. 1968, 162.000 Czechoslovak citizens came to Austria.

The scheme of the alleged airspace trespassing in Austria (MSFC, f. 1968)

On 26.9., the Austrian federal government decided to grant asylum to practically all of the applicants. However, the vast majority have eventually returned home, approximately 12 300 persons decided to leave for other countries, and ca 15 000 Czechs and Slovaks have remained in Austria.

Austrian media

had been quite closely informing on reforms and changes in Czechoslovakia ever since Dubček’s appointment. ORF would provide airtime not only to the genuine field commentaries but to Czechoslovak television’s programmes’ transmissions too. When Moscow accused the Austrian media of breaching the neutrality stance, the chancellor Klaus stated the Austrian media were not subjected to any governmental overview, and according to the laws any such control would be beyond the law.

Hugo Portisch, the iconic face of the ORF reports from behind of the Iron curtain, refers on Dubček’s reforms, in front of the Wenceslas square in Prague, May 1968 (ORF)

Students’ political activities in 1968

were of a great interest to me. Once I came across a such group of activists in a local student pub where they would plan a global revolution. They wanted to go to Floridsdorf to convince the workers to join the uprising. Yet it did not materialize due to the workers’ utmost lack of interest. Frankly, I t did not impress me much either. They would try to organize demonstrations in the Ringsstrase almost every day, yet in reality only a few people had attended. As for the student upheavals in Vienna, I reckon that the year 1968’s importance is quite far-fetched.

On invasion

We heard of it from the media, broadcasting and television, and of course, the newspapers. However, in the daily press, it would be presented as an internal Czech affair. The intention was to calm the population. Naturally, Austrians who lived nowhere near the border and who would not witness the heavy armoured tanks’ noise, were hardly aroused. However, people living near the border, were in much distress… They would certainly experience fear…

Mag. Werner Neuwirth (born in 1948, Thaya, Austria). From the archive of eye-wittness narratives from Austria. For GACY ’68: Hildegard Schmoller

It must have happened around 1959-1960,

it was rather a great sensation. A truck crashed through the Iron curtain. A man came in on the truck to the border. There were two bars there, so when it happened sometimes – which was a rare case – that someone was able to cross the border, had to stop in between the bars, enter the customs office, and were again able to continue only after managing certain technicalities. There were two bars and a real barbed wire fence, a fortress … little gates with barbed wire fence… and the guy on the truck simply crashed through it, broke the bars and drove on. … And of course, after the school we went to see it at the border with our very own eyes…

I entered the forces on April 1st ’68,

and at that time one could have felt that something was about to happen in politics… our then commander, first lieutenant, his name was Oberleitner, was raising awareness about what was happening behind the Iron curtain at that time. That … the rigid regime had started to loosen a bit… it must have been in April, at latest the beginning of May 1968… And then, everything happened. The Prague spring meant a significant change to us. … Dubček…, Brezhnev… We knew about it all, and yet suddenly, on 21st August, in the middle of the night the whole barracks got woken to: “Alert!”

Dr. Wolfgang Katzenschlager (born in 1943, Weitra, Austria). From the archive of eye-wittness narratives from Austria. For GACY ’68: Hildegard Schmoller

Panel 40

1 Karel Černoch, Bratislava Lyre, 1969 (AŠ)

2 Husák at the special KSS meeting, 28. 8. 19668 (SNM-HM e.č. H 56277/K. Cích)

3 The president of the republic in Bratislava, 29. 10. 1968 (TASR)

4 Dubček and Husák in dialogue after the signing of the federation act, 29. 10. 1968 (TASR)

5 Alexander Dubček in village Uhrovec, 10. 2. 1969 (TASR)

Husák’s speech

addressed at the extraordinary KPS meeting in Bratislava PKO, meant a turning point in the internal KSČ’s situation’s development. The very day following the invasion, all of the delegates had condemned it at the XIV session’s meeting in Prague. Such a decision is not very favourable for Moscow. Dubček as well as other KSČ representatives are dragged to Moscow. One must notice that one of the so called Moscow protocol’s features, which they are forced to sign, is that the Prague session’s outcomes are to be dissolved. When the dragged ones returned back home, the CC of KSČ adopted the Moscow protocol as a binding programme of the “situation’s normalization”. The Bratislava KSS meeting had begun on 26.8. when nothing had yet been decided on. It was right here where Husák, who had already returned “illuminated” from Moscow, declared, that the meeting in Vysočany was not legal, and thus a turn towards normalization could have begun. Until 17.4.1969, Dubček held the Party’s leading position. The photograph from the visit of his birthplace in Uhrovec, captured on 10.2. shows his yet ongoing popularity. However, in Moscow they already made up their minds. They picked Husák, and Dubček was “voluntarily” forced to resign. Cast aside at the position of the parliament’s chairman he was to last until September ’69, evicted to the embassy in Ankara, until June ’70. Husák had his era set be adjourned ad acta, while backing this move by Lessons Drawn from the Crisis Development in the Party and Society.

Panel 41

1 Educating for the Party’s purposes 1, 23. 10. 1969 (AŠ)

2 Reason : Stupidity, 2. 4. 1969 (AŠ)

3 Bratislava Lyre, Karel Kryl, June 1969 (AŠ)

4 Bratislava Lyre, Valéria Čižmárová, June 1969 (AŠ)

5 Tatra Revue, At the state’s expenses, 22. 9. 1965 (AŠ)

6 Legs and shadows, 6. 11. 1968 (AŠ)

Bratislava Lyre in 1969

was attended by Karel Kryl who had later emigrated, however, his songs would be circulated and sung at bone-fires. They have become a part of the ’68 myth, especially with the generations that have not experienced it. The stage at the Bratislava Lyre evoke the Sixty-eighth story’s very “leaving”. The scene itself reminds a gigantic swirl, a collapsar, the new reality’s black hole. A collapsar which by its huge gravitation force swallows down and decomposes everything what appears to be connected with the “era of hope”. Šmotlák’s fascination speaks to this very depth when photographing the performers. However, Karel Černoch’s picture is a peculiar one. At a first sight, it seems to be one of the thousands performer’s possible snapshots. Yet the composition of the photograph itself enables the observer to think differently, and set the very collapsar to the centre position, instead of the singer. Thus, Šmotlák’s snapshot aspires to a unique metaphor representing the very end of the Sixty-eighth’s story.: Černoch’s Song of my country, which won the contest, was full of painful references to the occupation, thus allowing us to brand it as a kind of a requiem for the very Sixty-eighth. The “new Reality’s” collapsar had swallowed both it and the performer.

Panel 42

1. Literal quotations from the letters written in the period of 1969 and 1970 (GACY)

2. A passage from the Canberra Times report from April 18th 1969, which refers to a gratulatory telegram of L. Brezhnev to G. Husák (NLA)

3. The writing from Zora Jesenská, in the ten years-old girl’s album, stating “may the courage be with you”, May 5th 1969 (MK)

4. A request of the cadre profile from April 17th 1972 (GACY)

5. Naša Univerzita journal’s front page, December 1973 (AUK)