1968: A Year We Should Not Forget …

Ľubor Matejko on the GACY’68 Project, as well as on how we remember the year 1968, and what we should not forget, concerning both Slovak and European circumstances

Ľubor Matejko (Commenius University in Bratislava), project coordinator

A Game-Changing Year 1968

——————————

You have chosen the Plato’s cave allegory as the project’s ‘motto’. Why?

Plato’s allegory describes people who, on the one hand, cannot or do not want to see and understand the world around them; and on the other hand, however, it tackles the people who are willing to transmit their own knowledge onto others. Stories similar to that of Plato’s have occurred many times in history and they are present even today. They show that knowledge can be stopped and prevented by neither by distrust or fear, nor simple reluctance to see the reality. Sometimes the stories do not end well for an individual, as was Plato’s case. However, not all the time.

How are we to understand the notion of seeing the reality instead its sole shadow?

The year 1968 is perceived by various people in various ways. While not exclusive, the generational aspect plays a significant role. Basically, our imagination is mainly determined by the structure of information received, thus adding to our very own jigsaw puzzle. This holds true even among those who experienced the ’68, since there were both things they were impacted by as well as things they barely noticed. In a way, it resembles a surrealist painting in which dreams and reality intertwine. Convincingly enough, in dreams, one may perceive even a shadow to be reality.

Do you attempt to disperse a dream from reality?

It’s more like I grasp their very relation to each other and accentuate the differences. Furthermore, the goal is to disperse the differing realities. One needs to acknowledge the importance of details, for starters. As an example: the very word reality occurred in Slovak newspapers with a capital ‘R’ after August 21st. People hardly remember nowadays, however then, this peculiar detail played an important role and people knew it very well. Even in Moscow they noticed. Not because they would somehow strongly be interested in Slovak orthography, rather they would realize this detail referred to a change in meaning of the very word ‘reality’. It signified the conflict of two realities… The new one had to be separated from that of yesterday.

Why then the year 1968?

Well, it is not just about the particular year 1968. I understand it rather as a social and cultural phenomenon. As such, it did not strictly take twelve months, and it influenced the lives of every family, street and town while at the same time it is a vital part of both our collective remembrance and identity. It is connected to events, values and figures, without which or whom we can hardly think of the contemporary Slovakia and Europe. From the perspective of collective remembrance, ’68 is unique, since people who experienced it still live among us, and yet it has been long enough for the archives to get accessible, thus providing us with what has been hidden for decades.

Show more

Memory constitutes an important part of an individual’s identity. Imagine there will be a time when doctors are able to transplant one’s brain. What would then happen to the patient after this operation, if their memory collided with the body’s memory, the corporeality? Let me now exaggerate a bit: a brain of a high jumper and a body of a weight lifter will not create a well-functioning structure. The same goes for society’s memory and identity: if you took its memory, they would not be alive and kicking. We all know that both European and Slovak identities are far from being fine-tuned. Yet we all wait for ‘someone’ to manage it … Thus we have buckled up and are ready to work.

Show less

What are the actual possibilities of archival research? Have we not found everything substantial yet?

Over the course of past ten years, many documents have been either published or made publicly accessible. However, the fact of their sole publicizing does not mean that they are exploited both in Slovakia as well as other EU countries. Moreover, the documents are far from being researched thoroughly, and debates on their interpretation are still going on.

What is the focus of your research?

We carry out genuine research at both the domestic and foreign archives. Since not all the issues are linked solely to Slovakia or Czechoslovakia, a foreign perspective sometimes brings more light on. Obviously, this holds true for both ‘big’ and ‘little’ history.

Show more

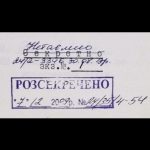

We are creating our very own archive of eyewitnesses’ personal memories and we, with our students, ‘sift through’ various Slovak archival funds. One may as well be surprised of the great deal of formerly unknown materials that we are to disclose. Our partners from Bologna University offered a research in Italian archives, Bulgarian, Croatian and Estonian partners will research their respective archives as well. We are also provided access to KGB Ukrainian archival funds’ documents.

Show less

What do you mean by the ‘big’ history?

It is the history written in politicians’ offices. The August 13th Brezhnev-Dubček phone call that occurred a week prior to the Soviet-lead invasion serves as a good example of it. Being a significant source, it describes a critical moment in the relationship between an imperial leader and its temporizing vassal.

What were they talking about?

Well, the talk took almost one hour and half, and one can feel an extraordinary emotional tension even from the transcription. While Brezhnev shows endurance in requiring “promise keeping”, as the two had settled on at both Čierna nad Tisou and Bratislava meetings, Dubček keeps on explaining, apologizing, or more precisely, making excuses, thus desperately trying to gain more time. He is losing control at times and even suggests his abdication.

Show more

The transcription includes, among many other things, this statement:

Dubček: If you think we are lying to you, take any necessary precautions you assume are needed. It is your business.

Brezhnev: You know what, Saša, we are certainly going to take the precautions we assume are needed… And you are right it is our business.

Show less

©GettyImages

Is it possible to understand Dubček’s words as an approval for intervention?

It is hard to tell what Dubček and Brezhnev understood as ‘precautions’, and if they understood it in the same way. Perhaps a record from the Čierna nad Tisou meeting would shed more light on it, however, no such record was made. To say the least, looking at the context of the conversation, we can hardly recognize Dubček’s words as an approval of a military intervention, let alone an invitation, even though there are tendencies to interpret them as such. His very manoeuvring clearly shows unwillingness to a voluntary surrender to his counterpart’s carefully-worded pressure, while solely accepting actions which both of them knew did not, as a matter of fact, require his distinct approval. Of course, he could have anticipated the danger of a military intervention. However, had it been the case, he could have hardly prepared his country for the worst, without him worsening the very situation.

What about the ‘little’ history? Do you mean the so-called ‘history from below’ as a counterpart to political or diplomatic history?

The reality of August 1968 is not solely constructed by the stories of Dubček, Brezhnev and Husák, who are a very much present in the textbooks. ‘Little’ history represents a huge field of undiscovered and unexploited archival documents. Also personal correspondence as a specific kind of source is to be mentioned here too. The letters disclose people’s most intimate emotions. You can’t find such information in the Political bureau’s resolutions. Unfortunately, many of those letters have ended up in trash cans.

So, is there a way to get the personal correspondence of the ordinary people?

Part of the letters which crossed the borders were captured by secret services, in order to be opened and noted down in a process called perlustration. However, one can find original letters here and there, lost and forgotten in old cupboards… For instance, such a case has brought us a letter describing the story of a former Banská Bystrica railway station officer. His name is not important, let us call him Joe Everyman. He got removed from his job in 1964 and offered a lower-ranking working class position as he presented internal Party materials on Gustáv Huská’s exculpation to his colleagues. A letter from the beginning of 1968 is an illustrative example of the then ordinary man’s feelings.

Before I dig into those feelings, perhaps you can explain the very cases of ‘Husák and Everyman’.

Husák was knocked out by a regime he himself had helped to establish. Once he became a liability, he got arrested and was held in ŠtB (secret service)’s detention from 1951 to 1954. After years of torture, he was eventually sentenced. He was released in 1960, however, it took him three additional years to get fully exculpated.

Show more

He actively started to participate in the Communist Party’s forums what caused substantial worries for the old upper echelons. And his activity harmed Joe Everyman. This “ordinary man” came across the Party’s bosses’ speeches copies, including those of Husák. It was nothing that would potentially have established any anti-communist sentiments, he himself was a communist. However, these materials were of a highly sensitive internal nature, showcasing a sign of the broken impeccability image of the Party. It was enough for Party Nomenclatura to punish him.

Show less

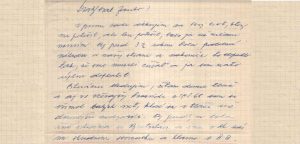

Let us go back to the letter. What does it tell us about the feelings of an ordinary man back in 1968?

Joe Everyman wrote his letter in January 1968, at the dawn of Husák’s ‘ascendance’. However, he already lived through feelings of bitterness, fear and distrust. In the letter, he replied to his brother who had ultimately tried to focus Everyman’s attention on future silver linings:

Joe Everyman is probably being sincere in his letter to his brother, it is, however, a single letter. Can we conclude the knowledge of ordinary people’s feelings accordingly?

Well, it shows the atmosphere of those times. Such a mixture of fear, shadiness and distrust was rather common. On the other hand, it in no way means that Joe Everyman would not laugh, love, go and see football matches, etc. Actually, it is not particularly about an emotion, as it is mostly about an attitude: to accept the state of mind where one differs between private and public lives, thus perceiving the state as a horrible instrument of power as opposed to an institution which ought to improve our lives instead. This very line of thought is often traceable within the eyewitnesses’ recordings.

Show more

By the way, the recordings refer to a distinct generation gap. The young ones tended to be much less sceptical back then in 1968; they would speak about hope, yet they recalled their parents’ distrust. The Joe Everyman in our story was about forty, so people of his generation are now about ninety-plus…. very few personal observers are still alive today. Their attitudes are solely accessible through recordings, letters or some other texts that were produced earlier. However, they dispose of one major weak side: one cannot ask about things not included.

Show less

Are you not bothered by the subjectivity of the personal observers’ stories?

It is always better to have some sources rather than none, particularly for historians. A research on memory needs to be accompanied by such stories, while their very subjectivity can be understood as an advantage. As a matter of fact, we actually expect them to be that way – a personal experience. Without the knowledge of people’s feelings, the image of reality tends to fade, thus resolving in a mere shadow, a colourless scheme with no taste or flavour. Such a scheme is rather very flexible. Take a look at the history textbooks and you may observe this very adjustment of a volatile scheme.

Nonetheless, the subjectivity has its limits…

Our storytelling, is influenced, regardless of our intentions, by a variety of generational, geographical, social or even personal circumstances… Social psychology would point out cognitive dissonance.

Show more

We tend to ‘improve’ the image of ourselves while talking about our experiences, thus manipulating that very image. Such cases, when performed during interviews, should draw our attention to dig a little further and get to know the reason why personal observers may remember things the way they do.

Show less

What are people talking the most about when asked about 1968?

Nowadays, most of the personal observers recall August 21st, in particular. This is usually the first and immediate response when starting the interview. Well, it makes sense, it was rather an impactful experience. The rest is only to emerge later, when dug more cautiously from their memory.

What is the image of August 1968 as perceived on the street?

A shock is what comes the most. Out of the many stories I know, one could create various mosaics, for instance:

Vrátnička v starej smaltovni na okraji hlavného mesta musela odovzdať služobnú pištoľ. Všade rachot a škrípanie železa, všetko sa otriasa. Ľudia vybiehajú z domov v pyžamách, iba redaktor nočného vydania populárnych novín spí tak tvrdo, že ho zobudí až búchanie na dvere. Do redakcie sa dobíja Kamil, ktorý prešiel krížom celé mesto a zdesil sa. Tanky, zmätok, virvar. Uprostred hukotu počuť často otázku „Počemu?“. Cudzinec v uniforme vyššieho dôstojníka, čo si pri jedinom moste cez Dunaj svieti baterkou do mapy, sa však pýta „Gde ulica Dostojevskogo?“ Nikto sa nedozvie uspokojujúcu odpoveď.

Show more

„Asi je vojna“, budí Štefana manželka ešte za tmy, uprostred dovolenky vo Vysokých Tatrách. Hneď ráno sa zbalia a cestujú domov. Čas sa nemeria na hodiny, ale na kilometre. Rady na benzínkach. Kolóny tankov zipsujú krajinu. Ľudia odmontujú obrovskú červenú hviezdu z brány Tatrasvitu a položia ju rovno na hlavnú cestu v nádeji, že sa zips zasekne. A naozaj, na moment sa to podarí… Kým dvaja vojaci neodložia hviezdu nabok. Potom sa vozidlá znova pohnú. Ďalší pokus. Hviezda opäť leží na ceste, ale tentoraz sa tanky pred ňou nezastavia. Tisíce márnych pokusov zastaviť vpád polmiliónovej armády, valiacej sa po zemi i zo vzduchu.

Archív UK: Zbierka fotografií – udalosti (21. august 1968), foto: Július Kiss, 1968

Krajina je hore nohami. Noviny vychádzajú v mimoriadnych vydaniach niekoľkokrát denne a zakaždým sa rozchytajú. V štátnom rozhlase znejú patetické výzvy. V éteri sa ozývajú stanice, ktoré predtým nevysielali. Pár dní nemajú ulice mená a smerové tabule sú pootáčané. Všade. Aj v obci Ďurkov ktosi iniciatívne urobil z úzkej vedľajšej uličky hlavnú dopravnú tepnu okresu. Malý Oňo pol dňa zíza cez škáru v plote na manévre vojenského konvoja, ktorý sa tu musí otočiť, lebo pred ním je už iba les.

©GettyImages

Archív UK: Zbierka fotografií – udalosti (21. august 1968), foto: Jozef Malacký, 1968

Na schodoch pred univerzitou v hlavnom meste Slovenska ležia kvety a Oľga zapaľuje sviečku. Štefan stojí v dlhočiznom rade na chlieb. Niekto iný na cukor, soľ, konzervy. Gabo kupuje dve piksle bielej farby a štetce. Ktosi zhodil pomník s hviezdou, ktorý pred rokmi postavili pri Pečnianskom jazere padlým z roku 1945…

Archív UK: Zbierka fotografií – udalosti (21. august 1968), foto: Jozef Malacký, 1968

Archív GACY’68, ©Ľudovít Števko, 1968

„Davaj radio“, zakričí cuciak v uniforme a chmatne plechovku s kusom trčiaceho drôtu, ktorú si šestnásťročný Laci drží pri uchu len preto, lebo má dobrý pocit, že niekoho nasrdí. Cuciak v uniforme má na čapici rovnakú hviezdu, ako bola tá na pomníku, aj tá na bráne Tatrasvitu.

Show less

The ‘Sixty-eight’ is not solely about August. How and why has the year 1968 become the ‘Sixty-eight’, particularly in Slovakia?

You are right, it is not just about the August. Many had perceived it that way since January when Alexander Dubček was elected the leader of the Communist party. For those better informed, the events had kicked off earlier, back in June 1967, when Ludvík Vaculík, Milan Kundera, and Antonín Liehm raised sharp criticism over the overall situation in Czechoslovakia at the Writers’ Union meeting. Undoubtedly, it was a message announcing a new wind blowing towards the Soviet empire’s periphery. Dubček himself would criticize his party boss Novotný, only to replace him the following year.

So, can we say that Sixty-eight already had begun in 1967?

Well, Sixty-eight also consists of a peculiar atmosphere of both political as well as cultural disturbances that had been formed for a much longer period of time. Should we understand it both socially and culturally, while at the same time admitting its universal impact, its roots can be found in the previous decade. In our country, this very phenomenon was born out of the thaw that had emerged after Stalin’s death. Stalin’s crimes and the personality cult’s criticism, prison releases and exculpations, added up to the overall thaw in Khrushchev’s USSR, most visibly after 1956. All of this had been experienced by Dubček first-hand, in Moscow. Few would be surprised as he had afterwards chosen to make exculpations his signature policy. However, Khrushchev was ‘laid off’ in 1964, thus giving way to the end of the Soviet Union’s thaw. In Czechoslovakia, while keeping up the pace in a rather lagging manner, with the thaw on track, we had been waiting for the events to reach their climax in 1968.

Was Dubček acquainted with Khrushchev?

Yes. Back in times when Dubček was ‘just’ the KSČ Slovak section’ leader, he welcomed Khrushchev in Banská Bystrica at the Slovak National Uprising’s twentieth anniversary. This meeting is even evidenced by a photograph which can easily be dubbed ‘The Unsuspecting’: there are two main ‘spring protagonists’ depicted in it: one, Khrushchev, could have hardly expected to be called off in the two months that followed; the other, Dubček, could have hardly expected to become the icon of yet another upcoming ‘spring’, only to find himself being ‘departed’ in its aftermath.

©GettyImages

So, Sixty-eight began in 1956?

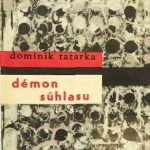

The beginning of Sixty-eight as a cultural phenomenon can easily be placed in 1956, even earlier. The very year, Tatarka’s The Demon of Consent, which spoke of the society’s demoralization as well as it fearful life, could have been read in the journal Kultúrny život.

Show more

In 1956, the Writers’ Union acknowledged a resolution which called on the abandonment of a ‘press supervision’ (as the censorship was once called) in arts, the exculpation of those unjustly convicted, etc. In addition, at the end of the fifties, a new spirit was emerging in music, inclining the young generation towards Western, particularly American, role models. Beginning in 1958, a Bratislava musical band, then known as Matuzalem, had enriched traditional tramp songs with Afro-American, as well as sacral elements. Ten years later, they would play beat music at masses.

The Pioneers’ palace, although previously a home for flamboyant performances of “The Internationale”, had suddenly opened up for rock ‘n’ roll… Let us call it the ‘greenhouse’ for Sixty-eight.

Show less

You mentioned the lagging in Czechoslovakia’s thaw…

Some political prisoners (with Husák among them) were released based on Novotný’s general pardon in relation to the new Socialist Constitution adopted in 1960. Yet another milestone was the former prisoners’ exculpation in 1963. At this point the thaw came (across) to our Joe Everyman. Quite paradoxically, this process was dubbed as ‘revitalization’. However, the same year, Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich’s Slovak translation became available, thus allowing amazed readers to ‘get to know’ the Gulag’s sufferings. The same year, Tatarka’s The Demon of Consent was published in the form of a book, leaving the Slovak audiences to enter a passionate debate.

The process of ‘revitalization’ is usually connected with Dubček’s era, though…

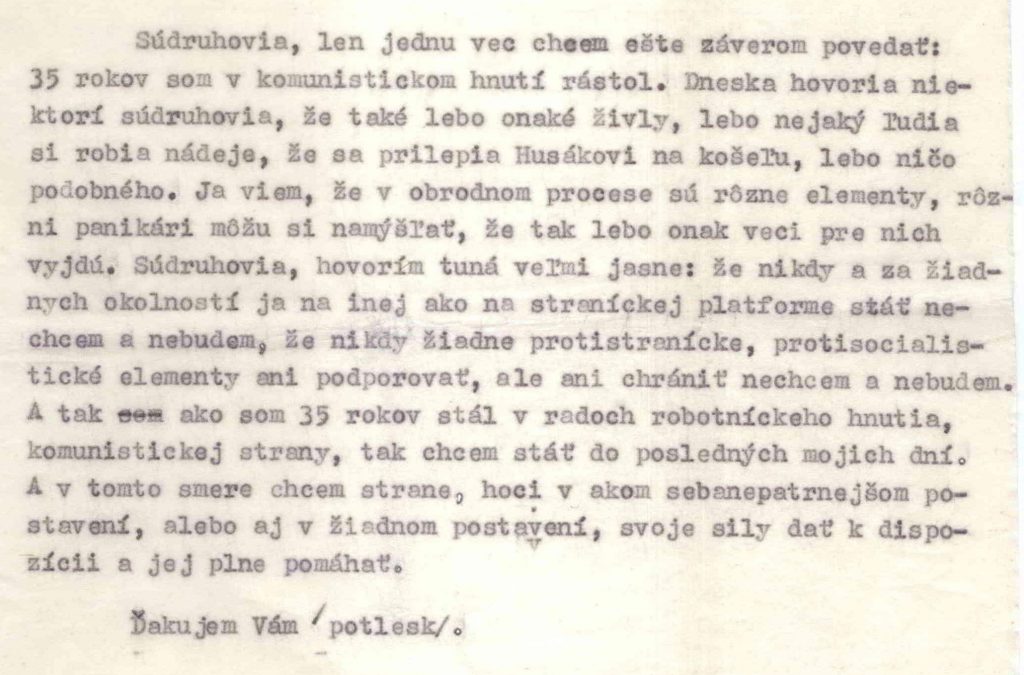

Sure, though, it is merely because during his era the process appeared to be at its climax. However, we have somehow forsaken its development. Contrary to the public’s perception, the term had been present in public discourse years earlier, mainly, due to the atonement of the personality cult’s crimes. For instance, Gustáv Husák used it within this framework in his speech in 1964, and while doing so, he was lessoned by the plenary chairman for exceeding the time limit. One must, however, point out that at this time Husák spoke as a mere participant. Nonetheless, it was a peculiar speech since it reflected the complexity of the vast reality.

Are you referring to the absurdity of Husák’s, first, initial intention to establish the very regime that had, later on, imprisoned him, only to, eventually, make him emerge as its very infamous protagonist of revitalization?

Well, yes indeed. On the other hand, one must accentuate his instrumental role during ‘normalization’, which had suppressed the very ‘revitalization’ process. However, were we to remember him solely as the ‘normalization’ figure, it would thus add to many situations which we tend to perceive through its ‘shadow’, while allowing us to think we actually see the reality. The ‘revitalization’ process, however, does not fully reflect the phenomenon of Sixty-eight either. Although contemporary discourse would commonly use the term, it had, nonetheless, produced a variety of layers which tend to appear only in hindsight. I, personally, find the term rather disturbing. If you feel the same way about it, well, it means we have troubles grasping it in this day and age. The term itself has to be attributed to the contemporary political discourse. As a matter of fact, to actually skip the simplification, one can further elaborate on its semantic interpretational layers too.

It resembles archaeology within linguistics…

The meaning of the term kept changing. Its oldest signifying layer had been established through the discussions on the atonement of ‘mistakes’ and ‘deformations’. Its youngest one had been formed during Dubček’s period. Yet at that time, it was not solely about formerly convicted communists’ exculpations, it appeared to include some other victims of the regime, such as priests, monks and clergymen. All in all, we talk about thousands of people. To a shocking extent, even Alexander Mach, the former Slovak state’s interior minister, had been released from prison on May 9th 1968 (the Victory Europe Day anniversary).

Show more

Initially, the ‘revitalization’ trickle had barely been perceivable by ordinary people, except for a scarce remark on the ‘personality cult’ included in the documents of the 10th KSČ congress from June 1954. It had, from time to time, been immersed, only to emerge later on, and yet again bolstered. Our railway station officer Joe Everyman was one of those who came across the very volatility of the ‘revitalization’ trickle in the flesh. His sole mistake was in the fact that he had wrongly assumed the ‘revitalization’ process’ true emergence as early as in 1964, instead of doing so as late as January ‘68.

Show less

Did the KSČ allow the church to be included in ‘revitalization’ process, even though it represented the archenemy of the regime? And what was even more striking, even a person convicted of war crimes?

Šaňo Mach – that is a case of its own. As for the churches, after Dubček’s accession, it somehow might have appeared as a logical step to take. Well, that added up to one of Sixty-eight’s profound symbols. A years-long plea for exculpations had naturally resulted in a general acceptance of a universal ethical norm: all victims were equal. The apparently atheist regime rendered policies previously unthought of. Let’s talk about two separate cases which may showcase the contemporary dynamics.

Show more

The first: Silvester Krčméry and Vladimír Jukl, were both significant figures of the Catholic dissent. They were imprisoned until 1964 and 1965 respectively. To their utter surprise, after being released from prison they found the church fully overtaken by the regime. Yet they had engaged in its reinstatement, while in 1966 they founded the first secret church university club. After the secret bishop Korec’s release in 1968, they began to institutionalize it, however, secretly. The very institutionalized secret church would then play a major role (with)in Slovak dissent during the seventies and eighties.

The second: Bishop Vasiľ Hopko was interned in his cloister in March 1968, where he experienced conditions similar to that of a prison. While experiencing his forced internment, he decided to write a letter in which he pleaded for the Greek Catholic church, forbidden as early as 1950, to be yet again permitted/reinstated. His plea resonated among other religious people as well as the Catholic episcopate, thus allowing tens of thousands of petitioners to accentuate the publicized reasoning (to reinstate the church). Even the papers referred to the sufferings that the Greek Catholics had undergone. Ladislav Holdoš, the Party dignitary most responsible for the church’s very liquidation back in 1950, who had in the meantime been imprisoned and later on exculpated, provided society with his testimony on ‘how the Greek Catholics became Orthodox Christians’, and already June 1968 witnessed the Greek church’s sudden permission. Well, the times were changing rather swiftly.

Show less

It seems a little strange that a Catholic, conservative and mostly rural Slovakia had so successfully been overtaken by the Communist regime.

I have mainly thought of the churches’ rather disastrous state, which was achieved by means of terror, imprisoning a great number of priests and monks, as well as nuns, or forcing them to ‘manual labour’, while threatening them in a constant manner. The result was the state’s full control over the churches. Many priests (had) failed to endure such a persistent pressure. On the other hand, atheization had unfolded. Collectivization and industrialization, among many other socially impactful processes, were responsible. During the twenty-five post-war years, the number of inhabitants in Bratislava, as well as other cities, had substantially grown, divorce numbers had risen as well… Slovaks no longer were that once rural community.

Joe Everyman’s letter discloses one interesting hint about regional differences: he considered Bratislava much more liberal than Banská Bystrica.

Naturally, one can easily notice the regional discrepancies. Therefore, our project attempts to perceive the various patterns of the ‘Prague Spring’ phenomenon as it emerged nationwide, while reinventing the long-forgotten stories deemed rather hidden due to the ‘normalization’ period. By the way, the aforementioned discrepancies held true throughout the whole country, mainly when speaking about the differences between the Czech and Slovak experiences. This very imbalance had constantly been present within people’s narratives. In other words, the Sixty-eight in Slovakia is hardly the same as that in the Czech lands.

Show more

At the beginning of the sixties, when Dubček was the head of KSS (Communist party of Slovakia), Bratislava had enjoyed a much looser atmosphere than in Prague. The Kultúrny život weekly published quite audaciously for contemporary standards. However, 1968 gave way to Prague. One must point out that Czechoslovakia, a formally unitary state, was far from homogenous concerning ethnic, social, economic or cultural aspects. August plays rather a unifying role within both Czech and Slovak narratives, while the pre- and post-August stories may differ, yet only to a certain extent. Two outstanding events, the abolishing of censorship and Jan Palach’s death, belong among the factors that had shaped both the Slovak and the Czech experiences.

Show less

What makes the Slovak Sixty-eight so peculiar?

The pre-August public discourse had been dominated by two main issues: democratization and federalization. The contemporary aphorism may, thus, have easily proclaimed ‘Democracy first, federation later’ on the Czech side, while Slovaks would point out the federation’s primacy, which would tend to intertwine with their very understanding of democracy. All in all, Dubček explained, in his conversation with Brezhnev, his failure to meet the ‘set targets’, by the federalization’s very own rather complicated approval procedures, thus referring to a form of democracy, in particular. As Petr Pithart would put it, Sixty-eight had been the result of both the Slovak national program and the Czech liberal intelligentsia’s endeavoured entanglements.

Show more

Well, one must admit that the more critical voice concerning Novotný’s regime had mostly been heard from Slovakia, well before 1967, while referring to the ‘Slovak issue’. Therefore, Dubček’s ascent might have been perceived by Slovak elites as a chance for raising the state’s federalization. While the democratization, although rather limited, was terminated by the events of August and its consequences, federalization had been formally achieved. However, initially, many would worry that it might not be delivered. The Slovak political elites’ satisfaction could thus help explain the differences in the stories unfolded by that very August’s ambiguity.

Show less

Archív UK: Zbierka fotografií – udalosti 21. august 1968, Foto: Jozef Malacký, 1968

What was the core of the ‘Slovak issue’?

During the sixties, the feeling of collective injustice which had predominantly been the reaction to Novotný’s regime’s inconsiderate handling of Slovak national myths, heroes and symbols. Imbalanced economic conditions had significantly added to its ever more accentuated perception. Those were, however, mainly eminent impulses. When looking for the systemic roots, one must acknowledge Czech-Slovak relations within their various shapes and forms found throughout the entire 20th century, or better, even immersed in the previous century.

Show more

You know, this would require a significantly longer time to explain. However, I will try to be brief. The 19th century bore witness to vast European nations’ modern nation-building processes. The Habsburg monarchy was no exception. While perceiving its dismemberment as a solution to its prolific nationalist squirmishes, Czechoslovakia, on the contrary, was far from doing so, thus ending up rather resembling the former empire’s miniaturized, even mirroring image, allowing solely, to a significant extent, the Czech nationalist programme to be pursued. Among many Czechs, millions of Germans and Slovaks, hundreds of thousands of Hungarians, Jews, Ukrainians and Poles had been living in one common state. The Slovak elites faced two options: either they would have to let their traditional nationalist agenda dissolve, or they would have to pursue it. This binary range would occupy the Slovak political discourse throughout the whole of the 20th century, only to let it prevail in the sixties.

Show less

And Novotný’s inconsiderate handling of myths and symbols? Well, that sounds like a political dropout…

It was a major strategical inconsideration and short-sightedness which, by the way, had much to do with collective ‘memory’ as well. Moreover, I reckon it might have resulted in rather negative patterns in Slovak society’s development. For instance, consider the discourse on our heroes, symbols, and identity.

Show more

The issue of Jozef Tiso had been banned from discussion twenty years before, as well as twenty years after Sixty-eight. There had been no public discussions, no seeking for guilt or responsibility, if you will. Thus, Slovak society was not provided a chance to come to terms, from within, regarding its own historical stains. Those had rather been exploited solely when the regime needed to dispose of someone… very purposefully. Even more strikingly, the same held true for the discourse on the Slovak National Uprising during the fifties! Furthermore, the new state’s coat of arms introduced in alignment with the new Constitution’s adoption in 1960, got rid of the Slovak double cross, while being replaced by a partisans’ bonfire beneath the Tatra mountain peaks, perched on the original Czech lion’s chest. No wonder it got dubbed ‘the barbeque below Kriváň mountain’. It is, therefore, this very context, within which one can only understand the peculiar mixture of conservativism a sentiment represented by the issue of a pin badge from 1968: a purposefully modified slogan of the French revolution intertwines with a long forbidden – however, nowadays ultimately natural – Slovak double cross.

Show less

You are assuming, given the bad economic situation of Slovakia, however, the whole country underwent such conditions.

You are right, the 3rd five-year plan had gone absolutely bankrupt. At the beginning of sixties, there was a lack of groceries, charcoal, etc… For this reason, economic reform was the ‘talk of the day’, and following Dubček’s ascent, no one doubted its introduction. Although the whole country suffered from (such) problems, both social and economic laggings were rather manifold, even more toxic in Slovakia, in comparison to the Czech part.

Show more

Slovakia, while being less urbanized and economically weaker, had kept lagging behind. Even more so, the gap kept on growing, since the economy was centrally planned and failing to recognize the very peculiarities of the urgency of Slovak development. There was a greater concentration of heavy industrial production in Slovakia, whereas most of the company headquarters were based in the Czech part, thus leading to an ever widening gap. However, it would require a separate chapter to elaborate on that.

Show less

Your project’s title stresses Czechoslovakia and Europe in 1968. Does our Sixty-eight have something in common with that of Europe?

Naturally, the circumstances are obvious. Well, Sixty-eight was predominantly about revolting, hope for change and great expectations. The same goes for (situations in) Paris, Berkeley and in our homeland. Both post-Stalinist Czechoslovakia as well as democratic countries were pre-occupied with calls for a fairer society and breaking (away) from the hypocrisy of power. People on both sides would face (the) weapons with flowers in their hands. Broadly speaking, the contemporary revolts presented particular attempts to shake the status quo which had been laid upon the world by the Cold War, a state which could be traced all the way back to the Second World War.

Was this happening despite the existence of the Iron Curtain?

The Iron Curtain had not been a hermetically impenetrable barrier, as one may have observed well before 1968, which was the year of a symbolic tear-down. Take a look at the fashion magazines, for instance… Or else, watch Nylon Moon from 1965 and you will find out that the young (generation/people) in Bratislava shared the same Beatlemania as (the young) those in Hamburg or London did. Consider Forman’s famous musical Hair which dealt with the generational conflict of the two Americas. You could have applied the same (logic) for Nylon Moon, however within a Bratislavan framework.

Show more

Hair was the ultimately unifying symbol. The socialist regime ‘put hair on notice’, as it penalized young (boys) men for wearing on long. However, you could have hardly found hippie communities, or the phenomenon of Wohngemeinschaften here, as one could observe in West Germany. The same would go for drugs: one could hardly observe their ubiquity here.

Show less

When you talk about the generational gap as a significant element in the youth’s revolt, how did it materialize in Czechoslovakia?

When it comes to Sixty-eight abroad, one tends to point out the conflict between the young generation which had come of age within the post-war television and rock ‘n’ roll realm, and the older one which had grown up within the inter-war radio and jazz realm. Our country provided similar conditions, however, they were rather dragged down by the totalitarian regime’s very inhibition of the development of the social order. Our youth’s representatives were particularly active, indeed, however, the resistance towards the existing order had not clearly been carried out with alignment to the generational lines. Furthermore, one could hardly dub the ‘revitalization process’s’ main protagonists as young.

To what extent can the Dubček’s ‘revitalization process’ be related to the imagery of the West where demonstrators would idolize Ho Chi Minh, Mao or Che Guevara?

Well, such an admiration of the aforementioned revolutionary figures simply could not have emerged in a country with its very own genuine communist experience. This might actually be the most striking difference between Sixty-eight in Czechoslovakia and in western liberal democracies: while students in Paris, Berlin or Berkeley would attack ‘traditional values and hierarchies’, here, it was their ‘revitalization’ that would pop up.

Show more

By the way, Dubček’s form of democratic socialism sounded quite a response in Europe, mainly in Bologna, where his cult (following) has kept on living till today. Rudi Dutschke, 28 years old, for instance, considered the Dubčekian political model to be a way of a ‘new mixture of socialism, individual freedom and democracy’. The August invasion caught many by surprise, while also causing shock and a feeling of sobriety.

Show less

France and Germany carried out a vast discussion on Sixty-eight’s legacy marking its recent anniversary. They were far from seamless…

May ’68 in Paris, students’ movements in Germany, demonstrations in Poland, Britain, Italy, the Netherlands, the United States, and Japan witnessed turbulent times. Regardless of its nature, Sixty-eight had undoubtedly brought dramatic change in both attitude and thinking.

Show more

One can trace its very impact on public reasoning as well as individual imaginations in the current European Union’s society. Highlighting ecology, feminism, multi-culturalism, a revolution in the relation between parents and teachers to children, or the nuclear family model’s shake-up – those had all emerged as mainstream attitudes in the following decades. These might actually show some significant differences between the two forms of the same Sixty-eight.

Show less

Can this very difference add up to the explanation of rather different attitudes in the so-called old and new member states’ elites?

Ordinary Soviet Bloc citizens could have hardly known in detail about the changes that western society underwent beginning in 1968. Even if they had noticed some differences in attitudes after the fall of the Iron Curtain, they would mostly not have understood them, or at best understand them in a peculiar way, while calling out the same European identity. In fact, they would miss the very two decades afterwards, that had shaped western thought. Take the ‘Greens’, for instance. While in the West, they have emerged as a major political party, here, one can barely notice their existence nowadays. Nowhere in the former Eastern Bloc does ecology play a significant role within the public discourse.

So, is this the outcome of August ’68 and the unfolded ‘normalization’?

August ’68 did not just mean the end of the Prague Spring, rather a constitutive exploitation of the energy of the whole generation’s incapacity. The ‘normalization’ made all forget everything connected with Sixty-eight, even the very ‘victory over the counter-revolution’. The ‘normalized’ Czechoslovakia would greatly celebrate the ‘victorious February’, the respective 1948 communist power takeover, however, the ‘victorious August’ had not been celebrated at all. No one would hang Brezhnev’s or Husák’s posters, no public candelabras would be decorated with red Soviet flags on Augusts 21st. Dubček’s very message had silently transformed to a myth, while dragging its contemporary protagonists along, only to return back to the disappointment of post-1989 reality. Well, this myth could have hardly served as a base for the road to social media and hip-hop.